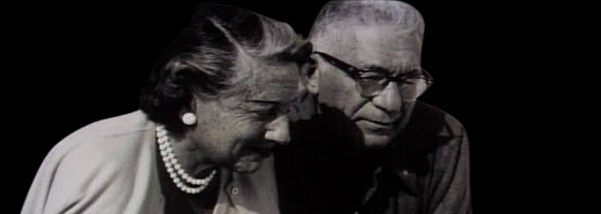

A VISIT WITH

GRANDMA PEARL

Interviews with

Pearl Weinhouse Gray

(1902 – 2000)

- Chapter 1: My Ancestors (Early 1800s – 1901)

- Chapter 2: Grandpa Eddie’s Ancestors

- Chapter 3: Grandpa Eddie’s Early Life (1892-1919)

- Chapter 4: My Childhood (1902-1918)

- Chapter 5: Meeting Grandpa Eddie (1919-1921)

- Chapter 6: Motherhood & Married Life (1922-1962)

- Chapter 7: Matriarch (1962 – 2000)

- Chapter 8: Looking Back at the Twentieth Century

- Chapter 9: Personal Reflections

Everybody wants to know where they sprang from, and who they are. This is a great void.

When I'm with family, I'm always reminiscing. If I get the ear of my children, and they are willing to listen, I try to inform them about my life. Because I figure, when I'm finished with my life, they won't hear any more. And if they hear it from me, they get the straight goods.

I don’t pontificate a lot. When I have delivered what I call “my lecture,” I’m gratified that they are interested in listening and say, "Oh, Grandma, I've never heard that story. I never knew that." Sometimes they're so incredulous that I knew about something or that I had this information. I’m always glad when they call me from somewhere; I keep them on the phone for an hour.

I learned the history because I wanted to hear it. I was interested in listening. I didn’t do all the talking because I feel that if you do all the talking, that’s all you hear – what you have said. You don’t learn anything.

As a small child, I was always delighted to sit for hours and listen to the older people just talking. I was so interested in knowing the background -- my attention span was endless. They’d tell funny little stories, sing songs, and talk about their life in Europe. I loved to hear the stories. It was something that I always wanted and was lucky enough to have people who would talk. I was very good at absorbing the stories. That’s why I know the history. When you put all these fragments together, you get a pretty good picture of who you are.

Chapter 1: My Ancestors (Early 1800s – 1901)

My father, Michael, was an immigrant from Russia. He and his family came in the latter part of the nineteenth century, but I don't remember hearing any dates. They never kept any records in Europe, so they were really short on a lot of their own history.

They had reasons for fleeing. It was either pogroms or some kind of persecution that brought them to America. They came to New York to Castle Garden, and then went directly to Chicago. Their whole family came with a group from Russia.

My father had a small cigar factory when he married my mother. He started his own factory and was successful in it. My grandfather didn't do too much of anything. In those days, “Papa” just sat there and the kids worked and brought in their little paychecks and gave it to him and to their mother. Mothers worked beside their husbands in the little shops. They didn't go out. They cooked and cleaned in the house and did whatever they had to do in the daily life.

My mother, Rebecca, was American born. She was born in St. Louis, Missouri. Her parents were named Simon Omensky and Bertha Trube. My grandmother was from Vinnitsa in Russia and my grandfather was from Odessa, a very lovely city in Europe on the Black Sea.

My grandfather came from more learned people. His forebears, down through the centuries, were all rabbinical people; they were the educated class. This was the highest thing, the best that you could be, because you were the teacher, the judge and the jury; you were a rabbi. But my great-grandmother, his mother’s family, were also very fine, high-class people. They were in some kind of business enterprise and had money.

The moneyed families usually tried to marry into the scholarly families. They would try to make those kind of matches, because the scholars didn’t have time for the money thing. If you were scholarly, you were studying with the chief rabbi, and that's a lifetime endeavor. You worked on that all your life.

My grandfather came from a very highly respected family. He was a very fine gentleman. I always say he looked like a Kentucky colonel. He was very knowledgeable, because they had trained him as a child, before he left when he was nineteen years old.

The reason my grandfather came to America is because he was the eldest son. In Russia, when the eldest son became old enough, he would go into the Czar's army. Once they got in there, they never knew when they were going to get out. This was a very toughening process.

You know what they used to do sometimes to Jewish boys? They would kidnap them from the villages. Some Cossack would be riding by on a horse, and scoop up a Jewish kid, and they would never see him again. Into the army he would go, and they never knew what became of him. Or else, a Cossack would be riding by, and for sport, he would hit kids with a big stick.

One of the comedians on the air, Joey Bishop, said his mother is blind in one eye as a result of some Cossack, when she was a child, playing this kind of sport. He rode by on a horse and hit her in the eye. And, of course, you never knew when they would come in full force, a whole bunch of drunken Cossacks, and create a pogrom. These were things that would happen!

Because Simon's father did not want him to serve for the Czar in the Russian army, he spirited him out of the country. His father decided that when he became eighteen years old and ready for the army, he would send him to America and save him from doing the service. A lot of them came for that reason at that particular moment in time.

Simon came in the latter part of the nineteenth century. It must have been in 1875. I do know that his parents knew that they would never see him again. They were not going to leave; they were going to stay there. They had to survive. But my grandfather's siblings all came. Families hung together.

He came with a group of people from there to St. Louis; they always went in groups. He left via the Black Sea and went through Turkey. They spent some time there and then they made their way, little by little, to Hamburg, Germany. And from there, they took a boat to Castle Garden, the place people came to before they created Ellis Island. The German-Jewish community was in this country first, and some of them were naturally able to help bring other Jews over.

They didn't tell me particularly about Russia -- they didn't sit me down and give me a history lesson. I had to assimilate this by osmosis. And of course, they all had stories to tell.

The hardships that they endured were unbelievable. Bertha’s mother, my great-grandmother, Ida, had some babies before Bertha. And they had a cholera epidemic in the town. The cholera epidemic wiped out whole communities. And I think she lost three babies. Her first children! Like I say, it's hair-raising. You can't believe that those things actually happened. And she almost lost her mind.

Now, when my grandmother, Bertha, was born, she got smallpox. They didn't have anything to treat people when smallpox would break out. You know, if you think about it, you can't believe it. But then again, there are backward nations today, countries where there's no medical stuff and where they die out like flies. The first thing you know there is a plague and it kills them out.

Ida went to the rabbi to find out if they could pray and keep her child from dying with the smallpox. Her parents had named her something else when she was born, but then the rabbi said that he was going to make some kind of blessing, and he told her mother to give her a new name, because then maybe God would overlook her. So, they named her Bruha. Bruha. That's a blessing. They figured that would be the thing that God would overlook and forget about and she would remain alive. Well, it so happened that she did remain alive, with the name of Bruha, which became Bertha in America.

Bertha had been married before she left Vinnitsa for America. And it was a very unhappy marriage. You know, women didn't have much choice when they got married. They had to take what they gave them. She must have been fifteen or sixteen years old when she married this man who was much older than her. After her marriage to him, she had a little boy baby, and became ill. And she was very unhappy with this man. So, they got divorced.

At about that point, she and her family -- the Trube family -- had a passage to come to America. Well, her husband was a very mean-spirited man and looking for revenge. He didn't want her to divorce him but she didn't want him, so it was a very bitter divorce. Since she was ill, she had a wetnurse for the baby. One day, when they were making plans now to leave for America, she was outside for a moment with the baby, who was in some kind of container. When she came back outside, the baby in that little basket was missing. And she knew that it was the father who kidnapped the baby.

It was awful, you know. There was trouble in the village and there were already signs of pogroms, so they had to leave without the baby. They had no choice because they didn't know where he was with that baby. He lived in a different village. And if they lived in a different village somewhere, it was like they lived on a different planet. And he had all the power. He could have stopped them all from leaving for America -- he could have gone to the authorities and made a complaint of some kind. So the whole family -- Bertha, her parents, and her two brothers, Charlie and Max -- left anyway.

I knew Bertha’s parents, Abraham and Ida. They were from Vinnitsa. It wasn’t a little village; it was quite a center. And they had an inn; they were innkeepers. That was their business there.

Arrival in St. Louis

They were immigrants and came to St. Louis from these different cities in Russia. When my grandmother came, Simon had already been in the country for awhile. Then they met and married.

They lived in a Jewish enclave in St. Louis that was like a little ghetto. The population was small, but they always stuck together, because they lived in a very hostile world when they came here. Yes, it was very hostile with anti-Semitism, so they hung together. And it was a little late in life for them to assimilate. They had their little shul where everybody went and they had their little kosher butcher stop. And they lived that way, on a smaller scale than Jews on the East Side in New York (that's where most of the population remained when they came to America). There was a place called Biddle Street – from the Biddle family, the early Philadelphia people. A lot of those street names were from pre-Civil War people in Philadelphia. At that particular time, they tried to settle Jews beyond the New York East Side. If you have any knowledge of that early history, theirs is the story of that early history.

Abraham and Ida came from Europe directly to St. Louis. They came without any worldly knowledge or experience. But they were hard working, modest people. My great-grandfather had been educated, but they didn’t teach him English. But he spoke English. He learned it and spoke it to make a living. See, a lot of those people became peddlers. They’d buy a little merchandise of some kind and go around and sell it door-to-door. And then after they saved up a few dollars they could buy a horse and a wagon, and then they were on their way. They had transportation and would go sell off the wagon. And at some point, they would find a little village somewhere that they liked and they'd open a little store.

They lived mostly together in little ghettoes. They'd have a little store and live in the back of the store, where there would be some space, or above it. And if you were married and had a wife, she was right beside you in the store. And the kids would help. Little by little, business became bigger, and pretty soon they had a big store. And that's the way it went. And in the early South, all these big department stores today, like Macy's, were peddlers in the beginning who then became big merchants.

When they came, they began to acquire little pieces of property. My great-grandparents had quite a bit of property. This is the way they sustained themselves. My great-grandmother, Ida, was running those little properties. I remember her going to the lawyer to pay her interest on the mortgages. Oh, yes, she was very smart. And she would dress herself with a bonnet – a typical Southern lady, if you have ever seen photographs of the way they looked in those days.

They came after the Civil War. General Grant had lived in St. Louis for a time during the Civil War. Abraham and Ida lived in a house that he had occupied in St. Louis. And there were slave quarters in the back of the house. When I was born, black, working people were still occupying those quarters, but they were not slaves anymore because it was after the Civil War and after slavery.

It was just a frame -- it was not real valuable property, but that was the best that they could afford. Abraham and Ida went there and collected the rent after they were home from working all day. I remember I used to be fearful of going to collect some of these rents. My grandmother, Bertha, would knock on the door and a little black lady, who had just been working all day long somewhere in service, would come to the door. She would give them whatever they could, if it was a quarter or half a dollar.

My mother was their first and only child, and she was born right there on the Mississippi River, where that arch is, and where my grandparents had a little second hand store. You see, the cotton people from the South would get on the little boat on the Mississippi River and sail up to St. Louis, which was the big city, at the north end, and they would bring their old furniture, their old clothing, everything, and sell it to these little store people. This is the way it was.

My grandfather Simon did different things. At one point, I remember, he told a story about how he learned to fit eye-glasses on people so they could read. He was an itinerant eye doctor and had a little satchel of stuff. They called him "Doctor." And he went to all the small towns. Farmers couldn't wait for the doctor to come, so he would fit them with glasses so that they could read.

Bertha’s Brothers

When they came here, Bertha had her two brothers. Charlie married and had two sons. He decided that he wanted to secure his future, so he took a job with the fire department. The fire department in St. Louis offered their firefighters retirement and pensions. That is what he did as a young man.

Her other brother, Max, married young when he was a teenager. He was a very enterprising, ambitious and successful merchant. He sold furniture. At first, just after the Civil War, there was a big market for second hand clothing, furniture, and all kinds of stuff. Then, he went to a little community across the river called Alton, Illinois, a small town, and he opened a store there. And then he became the mayor of the town. Yes. He became interested in politics too.

In those days, the fire department in town had horses for the fire apparatus. They had a wagon that was equipped with whatever they needed at the time. Remember, this is post Civil War. So, they came by his store one day and said, "Max, we are trying out a new motor-driven apparatus." They were in the process now of making changes.

"Would you please come and see what you think of it?"

He jumped on that fire truck and held onto the back, on a bar there. It was an opening thing where they had hoses and all the stuff. He jumped on the back and the thing moved. They came to a crossing and they hit a lamp post, an outside light. And when they hit that thing it knocked him off of the truck, and he hit his head, and it killed him.

He was forty-two years old. He would have probably become a Congressman. He had a very successful operation, a wife and four daughters. They lost him and then continued. His wife, Molly, was also his business partner. She was in the store. So, when he died, she had one married daughter and three other daughters. They were typical turn-of-the-century Southern ladies. Molly was from St. Louis, which was considered a Southern city. It was right on the edge but it was considered the South. It was situated on the Mississippi River.

There was also a boxer in Bertha's family who was a champion once, so there was a big thing going on in the family about that. You know a lot of those Jewish immigrants who first came here in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century became boxers. The champion came from a family of a bunch of boys who just drifted into that kind of thing; they were pretty good at it. They came with these Jewish names that they dropped immediately. Their name was White. The first one took the name Charlie White and then his brother took the name Jack White.

Keep reading: Chapter 2: Grandpa Eddie’s Ancestors